Still at the start of the John Ford filmography, I'm getting a chance to see the creation and experimentation of the director's technique, and I'm constantly surprised at the dichotomy among his movies as being either underwhelming or utterly spectacular. Before I started this queue through Ford history I was only acquainted with the films that made him famous, pictures like The Searchers (1956), She Wore A Yellow Ribbon (1949), My Darling Clementine (1946), etc. I love all of those movies and Ford sticks out as one of my favorite directors. My affection also created a set of expectations for him, and in the back of my brain I imagined every movie he made was as fantastic as the ones I already knew. I don't discredit myself for that either; it's natural to think everything a favorite director makes will be great. When I first began looking at film seriously (sometime in the late high school years), my as yet uninformed opinion told me that Scorsese was infallible, that he was The Best director hands-down. Then I started watching more movies and quickly realized that's a tough title to defend. Scorsese is still one of my favorites and I always find something singularly great in his movies, if not the entire picture itself, but for all of his influence he is not film's finest.

As I watch Ford's earlier obscure movies, like my experiences with Scorsese, there is something intriguing about all of them, too. They're not all masterpieces, but there is always something redeeming in them that catches my eye. It can be anything from a single shot composition or angle of light to the repeated use of an actor. Sometimes it's really not much, but there hasn't been one movie yet that didn't make me think about it historically, compositionally or otherwise. The two that are the subject of this post are good examples of the disparity in the overall product of his films; The Informer (1935) is an "experimental" work that plays with stylized lighting, camera work and sets; it's 100% "artistic," a trait Ford never liked put to his work, according to Joseph McBride's biography In Search of John Ford: A Life. McBride explains that Ford, as an emotionally-guarded Irishman insecure of his masculinity, defensively referred to his filmmaking as "work," not art. Mary of Scotland looks just as experimental for Ford as The Informer, with soft close-ups on Mary's (Katherine Hepburn) face contrasting with cavernous interior shots. What is striking about the latter film was a resemblance I noticed it had to Citizen Kane (1941) in terms of its low-angle camera placements and masterful use of shadow. On this note I should add that the cinematographer was not Gregg Toland (of Kane fame), but Joseph H. August, who worked with Ford again in 1945 on They Were Expendable. Toland took cinematography credit on two of Ford's films that did, however, precede Kane by one year in 1940, those are The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home.

The Informer and Mary of Scotland have a similar aesthetic that employs Ford's artistic experimentation, though the former is my favorite of the two, entirely due to its story.

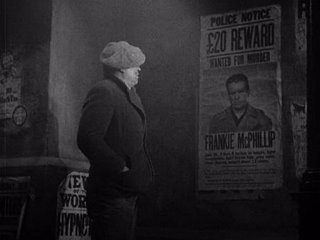

The Informer looks like a preface to The Grapes of Wrath; it is a socially-conscious film that follows a homeless, penniless man named Gypo (Victor McLaglen) (the name alone spells tragedy) who informs on his wanted friend to pick up reward money. We follow him through foggy streets of the Von Sternberg nature as his conscience eats at him for his desperate action. Yet the prospect of a 20 Pound reward gives him an alternative to starvation. Gypo blows the cash in one night, and his inner demons, as illustrated by the damp, shadowed streets, come out looking like a bad dream.

The Informer looks like a preface to The Grapes of Wrath; it is a socially-conscious film that follows a homeless, penniless man named Gypo (Victor McLaglen) (the name alone spells tragedy) who informs on his wanted friend to pick up reward money. We follow him through foggy streets of the Von Sternberg nature as his conscience eats at him for his desperate action. Yet the prospect of a 20 Pound reward gives him an alternative to starvation. Gypo blows the cash in one night, and his inner demons, as illustrated by the damp, shadowed streets, come out looking like a bad dream.  Mary of Scotland utilized massive sets that resembled the setup of live theater. Katherine Hepburn's intonation certainly hints at a higher, more affected way of speaking that's often associated with stage, and all of the character interactions felt physically awkward, as if they were choreographed for the stage, yet shot on film. What looked like a hint of Kane in this picture were the low-angle shots that threw off the balance of the set, making the ceilings look taller (though they were already tall on their own), and emphasized details of the mise-en-scene: big fireplaces, elaborate woodwork, costumes and tapestries. The endless adornments on set would seem to absorb the echoing space, but there remains plenty to spare.

Mary of Scotland utilized massive sets that resembled the setup of live theater. Katherine Hepburn's intonation certainly hints at a higher, more affected way of speaking that's often associated with stage, and all of the character interactions felt physically awkward, as if they were choreographed for the stage, yet shot on film. What looked like a hint of Kane in this picture were the low-angle shots that threw off the balance of the set, making the ceilings look taller (though they were already tall on their own), and emphasized details of the mise-en-scene: big fireplaces, elaborate woodwork, costumes and tapestries. The endless adornments on set would seem to absorb the echoing space, but there remains plenty to spare.Both of these films provide an historical thread that leads me to my Ford favorites of later days. One (The Informer) comes out on top as a favorite, while the other (Mary of Scotland) is a reference point for changes and experimentation in Ford's technique; both are valuable in understanding what came next.

What's next on the Ford queue? Young Mr. Lincoln (1939).

No comments:

Post a Comment